Lung cancer is a disease of uncontrolled cell growth in tissues of the lung. This growth may lead to metastasis, which is invasion of adjacent tissue and infiltration beyond the lungs. The vast majority of primary lung cancers are carcinomas of the lung, derived from epithelial cells. Lung cancer, the most common cause of cancer-related death in men and the second most common in women, is responsible for 1.3 million deaths worldwide annually. The most common symptoms are shortness of breath, coughing (including coughing up blood), and weight loss.

The main types of lung cancer are small cell lung carcinoma and non-small cell lung carcinoma. This distinction is important, because the treatment varies; non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) is sometimes treated with surgery, while small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) usually responds better to chemotherapy and radiation. The most common cause of lung cancer is long-term exposure to tobacco smoke. The occurrence of lung cancer in nonsmokers, who account for as many as 20% of cases, is often attributed to a combination of genetic factors, radon gas, asbestos, and air pollution, including secondhand smoke.

Lung cancer may be seen on chest x-ray and computed tomography (CT scan). The diagnosis is confirmed with a biopsy. This is usually performed via bronchoscopy or CT-guided biopsy. Treatment and prognosis depend upon the histological type of cancer, the stage (degree of spread), and the patient's performance status. Possible treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. With treatment, the five-year survival rate is 14%.Classification

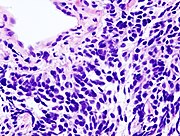

The vast majority of lung cancers are carcinomas—malignancies that arise from epithelial cells. There are two main types of lung carcinoma, categorized by the size and appearance of the malignant cells seen by a histopathologist under a microscope: non-small cell (80.4%) and small-cell (16.8%) lung carcinoma. This classification, based on histological criteria, has important implications for clinical management and prognosis of the disease.

Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC)

The non-small cell lung carcinomas are grouped together because their prognosis and management are similar. There are three main sub-types: squamous cell lung carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large cell lung carcinoma.Accounting for 31.1% of lung cancers, squamous cell lung carcinoma usually starts near a central bronchus. Cavitation and necrosis within the center of the cancer is a common finding. Well-differentiated squamous cell lung cancers often grow more slowly than other cancer types.

Adenocarcinoma accounts for 29.4% of lung cancers. It usually originates in peripheral lung tissue. Most cases of adenocarcinoma are associated with smoking; however, among people who have never smoked ("never-smokers"), adenocarcinoma is the most common form of lung cancer. A subtype of adenocarcinoma, the bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, is more common in female never-smokers, and may have different responses to treatment.

Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC)

Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC, also called "oat cell carcinoma") is less common. It tends to arise in the larger airways (primary and secondary bronchi) and grows rapidly, becoming quite large. The "oat" cell contains dense neurosecretory granules (vesicles containing neuroendocrine hormones), which give this an endocrine/paraneoplastic syndrome association. While initially more sensitive to chemotherapy, it ultimately carries a worse prognosis and is often metastatic at presentation. Small cell lung cancers are divided into limited stage and extensive stage disease. This type of lung cancer is strongly associated with smoking.

Metastatic cancers

The lung is a common place for metastasis from tumors in other parts of the body. These cancers are identified by the site of origin; thus, a breast cancer metastasis to the lung is still known as breast cancer. They often have a characteristic round appearance on chest x-ray. Primary lung cancers themselves most commonly metastasize to the adrenal glands, liver, brain, and bone.

Staging

Lung cancer staging is an assessment of the degree of spread of the cancer from its original source. It is an important factor affecting the prognosis and potential treatment of lung cancer. Non-small cell lung carcinoma is staged from IA ("one A"; best prognosis) to IV ("four"; worst prognosis). Small cell lung carcinoma is classified as limited stage if it is confined to one half of the chest and within the scope of a single radiotherapy field; otherwise, it is extensive stage.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms that suggest lung cancer include:

- dyspnea (shortness of breath)

- hemoptysis (coughing up blood)

- chronic coughing or change in regular coughing pattern

- wheezing

- chest pain or pain in the abdomen

- cachexia (weight loss), fatigue, and loss of appetite

- dysphonia (hoarse voice)

- clubbing of the fingernails (uncommon)

- dysphagia (difficulty swallowing).

If the cancer grows in the airway, it may obstruct airflow, causing breathing difficulties. This can lead to accumulation of secretions behind the blockage, predisposing the patient to pneumonia. Many lung cancers have a rich blood supply. The surface of the cancer may be fragile, leading to bleeding from the cancer into the airway. This blood may subsequently be coughed up.

Depending on the type of tumor, so-called paraneoplastic phenomena may initially attract attention to the disease. In lung cancer, these phenomena may include Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (muscle weakness due to auto-antibodies), hypercalcemia, or syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). Tumors in the top (apex) of the lung, known as Pancoast tumors, may invade the local part of the sympathetic nervous system, leading to changed sweating patterns and eye muscle problems (a combination known as Horner's syndrome) as well as muscle weakness in the hands due to invasion of the brachial plexus.

Many of the symptoms of lung cancer (bone pain, fever, and weight loss) are nonspecific; in the elderly, these may be attributed to comorbid illness.[5] In many patients, the cancer has already spread beyond the original site by the time they have symptoms and seek medical attention. Common sites of metastasis include the bone, such as the spine (causing back pain and occasionally spinal cord compression); the liver; and the brain. About 10% of people with lung cancer do not have symptoms at diagnosis; these cancers are incidentally found on routine chest x-rays.

Causes

The main causes of lung cancer (and cancer in general) include carcinogens (such as those in tobacco smoke), ionizing radiation, and viral infection. This exposure causes cumulative changes to the DNA in the tissue lining the bronchi of the lungs (the bronchial epithelium). As more tissue becomes damaged, eventually a cancer develops.

Smoking

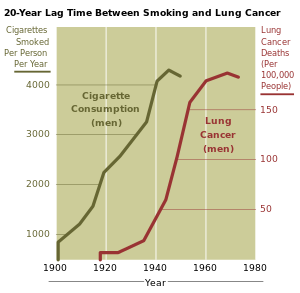

Smoking, particularly of cigarettes, is by far the main contributor to lung cancer. Across the developed world, almost 90% of lung cancer deaths are caused by smoking. In the United States, smoking is estimated to account for 87% of lung cancer cases (90% in men and 85% in women). Among male smokers, the lifetime risk of developing lung cancer is 17.2%; among female smokers, the risk is 11.6%. This risk is significantly lower in nonsmokers: 1.3% in men and 1.4% in women. Cigarette smoke contains over 60 known carcinogens, including radioisotopes from the radon decay sequence, nitrosamine, and benzopyrene. Additionally, nicotine appears to depress the immune response to malignant growths in exposed tissue.

The length of time a person smokes (as well as rate of smoking) increases the person's chance of developing lung cancer. If a person stops smoking, this chance steadily decreases as damage to the lungs is repaired and contaminant particles are gradually removed. In addition, there is evidence that lung cancer in never-smokers has a better prognosis than in smokers, and that patients who smoke at the time of diagnosis have shorter survival times than those who have quit.

Passive smoking—the inhalation of smoke from another's smoking—is a cause of lung cancer in nonsmokers. Studies have consistently shown a significant increase in relative risk among those exposed to passive smoke. Recent investigation of sidestream smoke suggests that it is more dangerous than direct smoke inhalation.

Radon gas

Radon is a colorless and odorless gas generated by the breakdown of radioactive radium, which in turn is the decay product of uranium, found in the earth's crust. The radiation decay products ionize genetic material, causing mutations that sometimes turn cancerous. Radon exposure is the second major cause of lung cancer, after smoking. Radon gas levels vary by locality and the composition of the underlying soil and rocks. For example, in areas such as Cornwall in the UK (which has granite as substrata), radon gas is a major problem, and buildings have to be force-ventilated with fans to lower radon gas concentrations. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that one in 15 homes in the U.S. has radon levels above the recommended guideline of 4 picocuries per liter (pCi/L) (148 Bq/m³). Iowa has the highest average radon concentration in the United States; studies performed there have demonstrated a 50% increased lung cancer risk, with prolonged radon exposure above the EPA's action level of 4 pCi/L.

Asbestos

Asbestos can cause a variety of lung diseases, including lung cancer. There is a synergistic effect between tobacco smoking and asbestos in the formation of lung cancer. In the UK, asbestos accounts for 2–3% of male lung cancer deaths. Asbestos can also cause cancer of the pleura, called mesothelioma (which is different from lung cancer).

Viruses

Viruses are known to cause lung cancer in animals, and recent evidence suggests similar potential in humans. Implicated viruses include human papillomavirus, JC virus, simian virus 40 (SV40), BK virus, and cytomegalovirus. These viruses may affect the cell cycle and inhibit apoptosis, allowing uncontrolled cell division.

Genetics

Similar to many other cancers, lung cancer is initiated by activation of oncogenes or inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. Oncogenes are genes that are believed to make people more susceptible to cancer. Proto-oncogenes are believed to turn into oncogenes when exposed to particular carcinogens. Mutations in the K-ras proto-oncogene are responsible for 10–30% of lung adenocarcinomas. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and tumor invasion. Mutations and amplification of EGFR are common in non-small cell lung cancer and provide the basis for treatment with EGFR-inhibitors. Her2/neu is affected less frequently. Chromosomal damage can lead to loss of heterozygosity. This can cause inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. Damage to chromosomes 3p, 5q, 13q, and 17p are particularly common in small cell lung carcinoma. The p53 tumor suppressor gene, located on chromosome 17p, is affected in 60-75% of cases. Other genes that are often mutated or amplificated are c-MET, NKX2-1, LKB1, PIK3CA, and BRAF.

Several genetic polymorphisms are associated with lung cancer. These include polymorphisms in genes coding for interleukin-1, cytochrome P450, apoptosis promoters such as caspase-8, and DNA repair molecules such as XRCC1. People with these polymorphisms are more likely to develop lung cancer after exposure to carcinogens.

Diagnosis

Performing a chest x-ray is the first step if a patient reports symptoms that may be suggestive of lung cancer. This may reveal an obvious mass, widening of the mediastinum (suggestive of spread to lymph nodes there), atelectasis (collapse), consolidation (pneumonia), or pleural effusion. If there are no x-ray findings but the suspicion is high (such as a heavy smoker with blood-stained sputum), bronchoscopy and/or a CT scan may provide the necessary information. Bronchoscopy or CT-guided biopsy is often used to identify the tumor type.

The differential diagnosis for patients who present with abnormalities on chest x-ray includes lung cancer as well as nonmalignant diseases. These include infectious causes such as tuberculosis or pneumonia, or inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis. These diseases can result in mediastinal lymphadenopathy or lung nodules, and sometimes mimic lung cancers. Lung cancer can also be an incidental finding: a solitary pulmonary nodule (also called a coin lesion) on a chest x-ray or CT scan taken for an unrelated reason.

Prevention

Prevention is the most cost-effective means of fighting lung cancer. While in most countries industrial and domestic carcinogens have been identified and banned, tobacco smoking is still widespread. Eliminating tobacco smoking is a primary goal in the prevention of lung cancer, and smoking cessation is an important preventative tool in this process.

Policy interventions to decrease passive smoking in public areas such as restaurants and workplaces have become more common in many Western countries, with California taking a lead in banning smoking in public establishments in 1998. Ireland played a similar role in Europe in 2004, followed by Italy and Norway in 2005, Scotland as well as several others in 2006, England in 2007, and France in 2008. New Zealand has banned smoking in public places as of 2004. The state of Bhutan has had a complete smoking ban since 2005. In many countries, pressure groups are campaigning for similar bans. In 2007, Chandigarh became the first city in India to become smoke-free.

Arguments cited against such bans are criminalisation of smoking, increased risk of smuggling, and the risk that such a ban cannot be enforced.

A 2008 study performed in over 75,000 middle-aged and elderly people demonstrated that the long-term use of supplemental multivitamins—such as vitamin C, vitamin E, and folate—did not reduce the risk of lung cancer. To the contrary, the study indicates that the long-term intake of high doses of vitamin E supplements may even increase the risk of lung cancer.

The World Health Organization has called for governments to institute a total ban on tobacco advertising in order to prevent young people from taking up smoking. They assess that such bans have reduced tobacco consumption by 16% where already instituted.

Treatment

Treatment for lung cancer depends on the cancer's specific cell type, how far it has spread, and the patient's performance status. Common treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

Surgery

If investigations confirm lung cancer, CT scan and often positron emission tomography (PET) are used to determine whether the disease is localised and amenable to surgery or whether it has spread to the point where it cannot be cured surgically.

Blood tests and spirometry (lung function testing) are also necessary to assess whether the patient is well enough to be operated on. If spirometry reveals poor respiratory reserve (often due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), surgery may be contraindicated.

Surgery itself has an operative death rate of about 4.4%, depending on the patient's lung function and other risk factors. Surgery is usually only an option in non-small cell lung carcinoma limited to one lung, up to stage IIIA. This is assessed with medical imaging (computed tomography, positron emission tomography). A sufficient preoperative respiratory reserve must be present to allow adequate lung function after the tissue is removed.

Procedures include wedge resection (removal of part of a lobe), segmentectomy (removal of an anatomic division of a particular lobe of the lung), lobectomy (one lobe), bilobectomy (two lobes), or pneumonectomy (whole lung). In patients with adequate respiratory reserve, lobectomy is the preferred option, as this minimizes the chance of local recurrence. If the patient does not have enough functional lung for this, wedge resection may be performed. Radioactive iodine brachytherapy at the margins of wedge excision may reduce recurrence to that of lobectomy.

Chemotherapy

Small cell lung carcinoma is treated primarily with chemotherapy and radiation, as surgery has no demonstrable influence on survival. Primary chemotherapy is also given in metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma.

The combination regimen depends on the tumor type. Non-small cell lung carcinoma is often treated with cisplatin or carboplatin, in combination with gemcitabine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, etoposide, or vinorelbine. In small cell lung carcinoma, cisplatin and etoposide are most commonly used. Combinations with carboplatin, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, vinorelbine, topotecan, and irinotecan are also used.

Adjuvant chemotherapy for NSCLC

Adjuvant chemotherapy refers to the use of chemotherapy after surgery to improve the outcome. During surgery, samples are taken from the lymph nodes. If these samples contain cancer, the patient has stage II or III disease. In this situation, adjuvant chemotherapy may improve survival by up to 15%. Standard practice is to offer platinum-based chemotherapy (including either cisplatin or carboplatin).

Adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage IB cancer is controversial, as clinical trials have not clearly demonstrated a survival benefit. Trials of preoperative chemotherapy (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) in resectable non-small cell lung carcinoma have been inconclusive.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is often given together with chemotherapy, and may be used with curative intent in patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma who are not eligible for surgery. This form of high intensity radiotherapy is called radical radiotherapy. A refinement of this technique is continuous hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy (CHART), in which a high dose of radiotherapy is given in a short time period. For small cell lung carcinoma cases that are potentially curable, chest radiation is often recommended in addition to chemotherapy. The use of adjuvant thoracic radiotherapy following curative intent surgery for non-small cell lung carcinoma is not well established and is controversial. Benefits, if any, may only be limited to those in whom the tumor has spread to the mediastinal lymph nodes.

For both non-small cell lung carcinoma and small cell lung carcinoma patients, smaller doses of radiation to the chest may be used for symptom control (palliative radiotherapy). Unlike other treatments, it is possible to deliver palliative radiotherapy without confirming the histological diagnosis of lung cancer.

Brachytherapy (localized radiotherapy) may be given directly inside the airway when cancer affects a short section of bronchus. It is used when inoperable lung cancer causes blockage of a large airway.

Patients with limited stage small cell lung carcinoma are usually given prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI). This is a type of radiotherapy to the brain, used to reduce the risk of metastasis. More recently, PCI has also been shown to be beneficial in those with extensive small cell lung cancer. In patients whose cancer has improved following a course of chemotherapy, PCI has been shown to reduce the cumulative risk of brain metastases within one year from 40.4% to 14.6%.

Recent improvements in targeting and imaging have led to the development of extracranial stereotactic radiation in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. In this form of radiation therapy, very high doses are delivered in a small number of sessions using stereotactic targeting techniques. Its use is primarily in patients who are not surgical candidates due to medical comorbidities.

Interventional radiology

Radiofrequency ablation should currently be considered an investigational technique in the treatment of bronchogenic carcinoma. It is done by inserting a small heat probe into the tumor to kill the tumor cells.

Targeted therapy

In recent years, various molecular targeted therapies have been developed for the treatment of advanced lung cancer. Gefitinib (Iressa) is one such drug, which targets the tyrosine kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R), expressed in many cases of non-small cell lung carcinoma. It was not shown to increase survival, although females, Asians, nonsmokers, and those with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma appear to derive the most benefit from gefitinib.

Erlotinib (Tarceva), another tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to increase survival in lung cancer patients and has recently been approved by the FDA for second-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. Similar to gefitinib, it also appeared to work best in females, Asians, nonsmokers, and those with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma.

The angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab, (in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin), improves the survival of patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. However, this increases the risk of lung bleeding, particularly in patients with squamous cell carcinoma.

Advances in cytotoxic drugs, pharmacogenetics and targeted drug design show promise. A number of targeted agents are at the early stages of clinical research, such as cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, the apoptosis promoter exisulind, proteasome inhibitors, bexarotene, and vaccines. Future areas of research include ras proto-oncogene inhibition, phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition, histone deacetylase inhibition, and tumor suppressor gene replacement.

Prognosis

Prognostic factors in non-small cell lung cancer include presence or absence of pulmonary symptoms, tumor size, cell type (histology), degree of spread (stage) and metastases to multiple lymph nodes, and vascular invasion. For patients with inoperable disease, prognosis is adversely affected by poor performance status and weight loss of more than 10%. Prognostic factors in small-cell lung cancer include performance status, gender, stage of disease, and involvement of the central nervous system or liver at the time of diagnosis.

For non-small cell lung carcinoma, prognosis is generally poor. Following complete surgical resection of stage IA disease, five-year survival is 67%. With stage IB disease, five-year survival is 57%. The five-year survival rate of patients with stage IV NSCLC is about 1%.

For small cell lung carcinoma, prognosis is also generally poor. The overall five-year survival for patients with SCLC is about 5%. Patients with extensive-stage SCLC have an average five-year survival rate of less than 1%. The median survival time for limited-stage disease is 20 months, with a five-year survival rate of 20%.

According to data provided by the National Cancer Institute, the median age of incidence of lung cancer is 70 years, and the median age of death by lung cancer is 71 years.

No comments:

Post a Comment