Ever since their discovery, both the Neanderthals' place in the human family tree and their relation to modern Europeans have been hotly debated. At different times they have been classified as a separate species (Homo neanderthalensis) and as a subspecies of Homo sapiens (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis).

Anthropologists advanced and still advance arguments favoring either an accelerated regional evolution of Neanderthal towards Homo Sapiens, or interbreeding with or replacement by anatomically modern humans. There is no agreement on the association of early Aurignacian culture to any specific physical human type, including figurative art found at Vogelherd. The interpretation of the Neanderthal Genome Project results so far vary from a 0.1% contribution of Neanderthal to the modern gene pool, to a genetic similarity not unlike two extant members of one referenced population in West Africa.

The obvious anatomic differences between Neanderthal and anatomically modern humans inspired the general belief in two separate branches of the genus Homo, and favored the single-origin hypothesis in that modern humans are not directly descended from the Neanderthal branch. The nature of interaction and dividing lines between Neanderthal and archaic Homo Sapiens during the period 50,000 to 25,000 years ago remain largely unknown. Though it has been suggested that the late Neanderthal populations survived in Southern Iberia, in general this area has been considered a "cul-de-sac", playing a passive role in human/biological evolution. There is considerable debate about whether Cro-Magnon people accelerated the demise of the Neanderthals, and many hypotheses to that extent are currently available.

Extinction scenarios

Rapid extinction

Jared Diamond has suggested a scenario of violent conflict comparable to the genocides suffered by indigenous peoples in recent human history. Another possibility, paralleling colonialist history, would be a greater susceptibility to pathogens introduced by Cro-Magnon man on the part of the Neanderthals. Although Jared Diamond and others have specifically mentioned Cro-Magnon diseases as a threat to Neanderthals, this aspect of the analogy with the contacts between colonisers and indigenous peoples in recent history can be misleading.[original research?] The distinction arises because Cro-Magnons and Neanderthals are both believed probably to have lived a nomadic lifestyle, whereas in those genocides of the colonial era in which differential disease susceptibility was most significant, it resulted from the contact between colonists with a long history of agriculture and nomadic hunter-gatherer peoples. Diamond argues that asymmetry in susceptibility to pathogens is a consequence of the difference in lifestyle, which makes it irrelevant in the context of the analogy in which he invokes it.

On the other hand, many Native Americans before contact with Europeans were not nomadic, but agriculturalists (Mayans, Iroquois, Cherokee), and this still did not protect them from the disease epidemics brought by Europeans (Smallpox). One theory is that because they usually lacked large domesticated animal agriculture, such as cows or pigs in close contact with people (Zoonosis), they did not develop resistance to species-jumping diseases like Europeans had.

Gradual extinction

However, these scenarios may be more drastic than is required to explain a decline of Neanderthal population over the course of some 10,000-20,000 years: even a slight selective advantage on the part of modern humans could account for Neanderthals' replacement on such a timescale. Gradual climatic change as a cause of extinction is also a common hypothesis. Speech-related theories have been largely discredited.

The problem with a gradual extinction scenario lies in the resolution of dating methods. There have been claims for young Neanderthal sites, younger than 30,000 years old. Even claims for interstratification of Neanderthal and modern human remains have been advanced. So the fact that Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted at least for some time seems certain. However, because of difficulties in calibrating the C14 dates the duration of this period is uncertain.

Interaction with Cro-Magnons

Interaction may have occurred at any time along the fringes of the Neanderthal expanse, and ultimately anywhere they met with the Cro Magnon advance. As for now, the expansion of the first anatomically modern humans into Europe can't be located by diagnostic and well-dated anatomically modern human fossils "west of the Iron Gates of the Danube" before 32 kya. In Lagar Velho Neanderthal skeletons of younger dating have been found with mixed traits, in Southern Iberia.

The genetic variation at the microcephalin gene, a critical regulator of brain size whose loss-of-function by damaging mutations may also cause primary microcephaly, is claimed to be the most compelling evidence of admixture thus far. One type of the gene, dubbed haplogroup D having an exceptionally high worldwide frequency (~70%), was shown to have a remarkably young coalescence age to its most recent common ancestor ~37,000 years ago. The remaining types (non-D) coalesce to ~990,000 years ago, while the separation time between D and non-D was estimated at ~1,100,000 years ago. An evolutionary advance was assumed, even though positive selection was never as all-decisive as to wipe out the remaining 30% of non-D haplogroups (in which case no introgression could have been suggested) and as for now, a measurable genetic advance has not been attested. Both the worldwide frequency distribution of the D allele, exceptionally high outside of Africa but low in sub-Saharan Africa (29%) that suggests involvement of an archaic Eurasian population, and current estimates of the divergence time between modern humans and Neanderthals based on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), are in favor of the Neanderthal lineage as the most likely archaic Homo population from which introgression into the modern human gene pool took place.

The case for fertile reproduction recently revived by studies that claim signs of admixture (introgression), finding unusually deep genealogies in highly divergent clades (genetic branches). However, most of the times this feature can be explained by balancing selection. For instance, estimates on the gene for red hair vary from 20,000 to 100,000 years ago, though there is no compelling evidence to assume red hair didn't coexist with other hair colours all along within one and the same population. Moreover, Lalueza-Fox and colleagues found a different variant of the same gene in their Neanderthal samples, that similarly disabled a protein to the same effect.

Interbreeding

There is another hypothesis that the Neanderthals were absorbed into the Cro-Magnon population by interbreeding. This scenario would render the Recent African Origin scenario obsolete in favour of a hybrid-origin scenario, since it would imply that at least a minor fraction of the genome of Europeans would descend from Neanderthals, who had left Africa at least 350,000 years ago. No evidence supporting this scenario has been found in mtDNA analysis of modern Europeans, suggesting at least that no direct maternal line originating with Neanderthals has survived into modern times.

The most vocal proponent of the hybridization hypothesis is Erik Trinkaus of Washington University. Trinkaus claims various fossils as hybrid individuals, including the "child of Lagar Velho", a skeleton found at Lagar Velho in Portugal dated to about 24,000 years ago. In a 2006 publication co-authored by Trinkaus, the fossils found in 1952 in the cave of Pestera Muierii, Romania, are likewise claimed as hybrids.

Based on an Oxford University 2001 study of the gene that results in red-headedness, some commentators speculated that Neanderthals had red hair and that some red-headed and freckled humans today share some heritage with Neanderthals. A 2007 study analysing Neanderthal DNA found that some Neanderthals were indeed red-haired, but the mutation to the MC1R gene which caused red hair in Neanderthals was different from that found in modern individuals, possibly ruling out that red hair is a trait inherited from the Neanderthals.

Unable to adapt

European populations of H. neanderthalensis have been traditionally thought to be adapted to a cold environment, and thus may have had problems adapting to a warming environment. This may or may not be the case, although it has been suggested that the difference in cold-adaptation between Neanderthals and H. sapiens may have been minor.

Another possibility has to do with the loss of the Neanderthal's primary hunting territory - forests. The Neanderthals hunted by stabbing their prey with spears (as opposed to throwing the spears at their prey). They were also far less mobile than modern humans. Thus when the forests were gradually replaced by flat lands, the Neanderthals would have had great difficulty hunting. In the open they would not have been able to stalk their prey, their stabbing weapons would have been largely useless, and they - unlike modern humans - could not easily chase their prey. The heavily-set build of the Neanderthals also suggests that they may have had large energy requirements, therefore if their method of hunting became less efficient (as described above) the increased energy expenditure may have been too much to sustain.

Division of labor

In 2006, anthropologists Steven L. Kuhn and Mary C. Stiner of the University of Arizona proposed a new explanation for the demise of the Neanderthals. In an article titled "What's a Mother to Do? The Division of Labor among Neanderthals and Modern Humans in Eurasia", they theorise that Neanderthals like Middle paleolithic Homo sapiens did not have a division of labor between the sexes. Both male and female Neanderthals participated in the single main occupation of hunting big game that flourished in Europe in the ice age like bison, deer, gazelles and wild horses. This contrasted with humans who were better able to use the resources of the environment because of a division of labor with the women going after small game and gathering plant foods. In addition because big game hunting was so dangerous this made humans, at least males, more resilient.

Anatomical differences and running ability

Researches including Karen L. Steudel of the University of Wisconsin have proposed that because Neanderthals had limbs that were shorter and stockier than modern humans, and because of anatomical differences in their limbs, it is theorized that the primary reason the Neanderthals were not able to survive is related to the fact that they could not run as fast as modern humans, and they would require 30% more energy than modern humans would for running or walking. This would have given modern humans a huge advantage in battle. Other researchers, like Yoel Rak, from Tel-Aviv University, Israel have noted that the fossil records show that Neanderthals pelvises in comparison to modern human pelvises would have made it much harder for Neanderthals to absorb shock and to bounce off from one step to the next, giving modern humans another advantage over Neanderthals in running and walking ability.

Neanderthals failed to adapt to the Ice Age

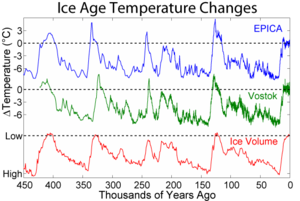

According to this hypothesis the inability to adapt to climate change led to the Neandertals' demise. Not the cold, since both Cro Magnons and Neandertals had clothing, but failure to adapt their hunting methods caused their extinction when Europe changed into a sparsely vegetated steppe and half desert during the last Ice Age.

In popular culture

- Jean M. Auel's book The Clan of the Cave Bear, and to some extent other books in the series Earth's Children, fictionally explore the lives and cultures of Neanderthals and Cro-magnons co-existing in Europe.

- The fantasy novelist Jack Vance, in his Lyonesse Trilogy, mentions that cannibal Neanderthals battled with the ancient ancestors of the Ska, an imaginary culture or subspecies of Homo sapiens.

- Science fiction novelist Larry Niven speculates that encounters with Neanderthals was the basis for human folklore about trolls, ogres, and suchlike.

- Michael Crichton's novel, Next contains a series of articles describing the extinction of the apparently more intelligent Neanderthals with comparison with Homo sapiens.

- William Golding's second novel, The Inheritors reconstructs the life of Neanderthal interaction and subsequent extinction with a "newly-evolved" malevolent Homo sapiens species.

- The novel Dance of the Tiger by paleontologist Björn Kurtén explores Neanderthal and Cro-magnon integration.

- The Neanderthals appear in the movie directed by Shawn Levy "Night at the Museum". They are however incorrectly depicted as a species that lacked complex language, and couldn't control fire.

- The Neanderthal Parallax - a trilogy of novels by Robert J. Sawyer - shows the effects of the opening of a connection between two alternate Earths: the world familiar to the reader, and another where Neanderthals became the dominant, sentient hominid. The societal, spiritual and technological differences between the two worlds form the focus of the story.

- Jasper Fforde's novel, Lost in a Good Book contains many clones of extinct animals. It also features cloned Neanderthals, who are treated as subhuman, but who actually are very peace-loving and cultured.

No comments:

Post a Comment