Overview

The kidneys are a pair of organs that are primarily responsible for filtering metabolites and minerals from the circulatory system. These secretions are then passed to the bladder and out of the body as urine. Some of the substances found in urine are able to crystalize, and in a concentrated form these chemicals can precipitate into a solid deposit attached to the kidney walls. These crystals can grow through a process of accretion to form a kidney stone. In medical terminology these deposits are known as renal calculi.

Renal calculi can vary in size from as small as grains of sand to as large as a golf ball. Kidney stones typically leave the body by passage in the urine stream, and many stones are formed and passed without causing symptoms. If stones grow to sufficient size before passage—on the order of at least 2-3 millimeters—they can cause obstruction of the ureter. The resulting obstruction with dilation or stretching of the upper ureter and renal pelvis as well as spasm of muscle, trying to move the stone, can cause severe episodic pain, most commonly felt in the flank, lower abdomen and groin (a condition called renal colic). Renal colic can be associated with nausea and vomiting due to the embryological association of the kidneys with the intestinal tract. Hematuria (bloody urine) is commonly present due to damage to the lining of the urinary tract.

The incidence rate increases to 20–25%, because of increased risk of dehydration in hot climates.Men are affected approximately 4 times more often than women. Recent evidence has shown an increase in pediatric cases.Causes

Kidney stones can be due to underlying metabolic conditions, such as renal tubular acidosis, Dent's disease and medullary sponge kidney. Many health facilities will screen for such disorders in patients with recurrent kidney stones. This is typically done with a 24 hour urine collection that is chemically analyzed for deficiencies and excesses that promote stone formation. Kidney stones are also more common in patients with Crohn's disease.

There has been some evidence that water fluoridation may increase the risk of kidney stone formation. In one study, patients with symptoms of skeletal fluorosis were 4.6 times as likely to develop kidney stones. However, fluoride may also be an inhibitor of urinary stone formation.

There is a longstanding belief among the mainstream medical community that vitamin C causes kidney stones, which may be based on little science. Although some individual recent studies have found a relationship there is no clear relationship between excess ascorbic acid intake and kidney stone formation.

Calcium oxalate stones

The most common type of kidney stone is composed of calcium oxalate crystals, occurring in about 80% of cases, and the factors that promote the precipitation of crystals in the urine are associated with the development of these stones.

Common sense has long held that consumption of too much calcium could promote the development of calcium kidney stones. However, current evidence suggests that the consumption of low-calcium diets is actually associated with a higher overall risk for the development of kidney stones. This is perhaps related to the role of calcium in binding ingested oxalate in the gastrointestinal tract. As the amount of calcium intake decreases, the amount of oxalate available for absorption into the bloodstream increases; this oxalate is then excreted in greater amounts into the urine by the kidneys. In the urine, oxalate is a very strong promoter of calcium oxalate precipitation, about 15 times stronger than calcium.

Uric acid (urate)

About 5–10% of all stones are formed from uric acid. Uric acid stones form in association with conditions that cause hyperuricosuria with or without high blood serum uric acid levels (hyperuricemia); and with acid/base metabolism disorders where the urine is excessively acidic (low pH) resulting in uric acid precipitation. A diagnosis of uric acid nephrolithiasis is supported if there is a radiolucent stone, a persistent undue urine acidity, and uric acid crystals in fresh urine samples.

Other types

Other types of kidney stones are composed of struvite (magnesium, ammonium and phosphate); calcium phosphate; and cystine.

The formation of struvite stones is associated with the presence of urea-splitting bacteria, most commonly Proteus mirabilis (but also Klebsiella, Serratia, Providencia species). These organisms are capable of splitting urea into ammonia, decreasing the acidity of the urine and resulting in favorable conditions for the formation of struvite stones. Struvite stones are always associated with urinary tract infections.

The formation of calcium phosphate stones is associated with conditions such as hyperparathyroidism and renal tubular acidosis.

Formation of cystine stones is uniquely associated with people suffering from cystinuria, who accumulate cystine in their urine.

Symptoms

Symptoms of kidney stones include:

- Colicky pain: "loin to groin". Often described as "the worst pain ever experienced".

- Hematuria: blood in the urine, due to minor damage to inside wall of kidney, ureter and/or urethra.

- Pyuria: pus in the urine.

- Dysuria: burning on urination when passing stones (rare). More typical of infection.

- Oliguria: reduced urinary volume caused by obstruction of the bladder or urethra by stone, or extremely rarely, simultaneous obstruction of both ureters by a stone.

- Abdominal distention.

- Nausea/vomiting: embryological link with intestine – stimulates the vomiting center.

- Fever and chills.

- Hydronephrosis

- Postrenal azotemia: when kidney stone blocks ureter

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis is usually made on the basis of the location and severity of the pain, which is typically colic in nature (comes and goes in spasmodic waves). Pain in the back occurs when calculi produce an obstruction in the kidney.

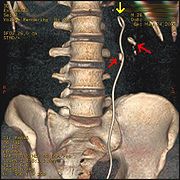

Imaging is used to confirm the diagnosis and a number of other tests can be undertaken to help establish both the possible cause and consequences of the stone. Ultrasound imaging is also useful as it will give details about the presence of hydronephrosis (swelling of the kidney). It can also be used to show the kidneys during pregnancy when standard x-rays are discouraged. About 10% of stones do not have enough calcium to be seen on standard x-rays (radiolucent stones) and may show up on ultrasound although they typically are seen on CT scans.

The relatively dense calcium renders these stones radio-opaque and they can be detected by a traditional X-ray of the abdomen that includes the Kidneys, Ureters and Bladder—KUB. This may be followed by an IVP (Intravenous Pyelogram; (IntraVenous Urogram (IVU) is the same test by another name)) which requires about 50 ml of a special dye to be injected into the bloodstream that is excreted by the kidneys and by its density helps outline any stone on a repeated X-ray. These can also be detected by a Retrograde pyelogram where similar "dye" is injected directly into the ureteral opening in the bladder by a surgeon, usually a urologist.

Computed tomography (CT or CAT scan), a specialized X-ray, is considered the gold-standard diagnostic test for the detection of kidney stones, and in this setting does not require the use of intravenous contrast, which carries some risk in certain people (eg, allergy, kidney damage). All stones are detectable by CT except very rare stones composed of certain drug residues in the urine. The non-contrast "renal colic study" CT scan has become the standard test for the immediate diagnosis of flank pain typical of a kidney stone. If positive for stones, a single standard x-ray of the abdomen (KUB) is recommended. This additional x-ray provides the physicians with a clearer idea of the exact size and shape of the stone as well as its surgical orientation. Further, it makes it simple to follow the progress of the stone without the need for the much more expensive CT scan just by doing another single x-ray at some point in the future.

Other investigations typically carried out include:

- Microscopic study of urine, which may show proteins, red blood cells, bacteria, cellular casts and crystals.

- Culture of a urine sample to exclude urine infection (either as a differential cause of the patient's pain, or secondary to the presence of a stone)

- Blood tests: Full blood count for the presence of a raised white cell count (Neutrophilia) suggestive of infection, a check of renal function and to look for abnormally high blood calcium blood levels (hypercalcaemia).

- 24 hour urine collection to measure total daily urinary volume, magnesium, sodium, uric acid, calcium, citrate, oxalate and phosphate.

- Catching of passed stones at home (usually by urinating through a tea strainer) for later examination and evaluation by a doctor.

Treatment

Temporizing

About 90% of stones 4 mm or less in size usually will pass spontaneously, however 99% of stones larger than 6 mm will require some form of intervention. There are various measures that can be used to encourage the passage of a stone. These can include increased hydration, medication for treating infection and reducing pain, and diuretics to encourage urine flow and prevent further stone formation. Eating starfruit can be effective at reducing pain and improving urination. However caution should be exercised due to other concerns with the ingestion of starfruit.

In most cases, a smaller stone that is not symptomatic is often given up to four weeks to move or pass before consideration is given to any surgical intervention as it has been found that waiting longer tends to lead to additional complications. Immediate surgery may be required in certain situations such as in people with only one working kidney, intractable pain or in the presence of an infected kidney blocked by a stone which can rapidly cause severe sepsis and toxic shock.

Analgesia

Management of pain from kidney stones varies from country to country and even from physician to physician, but usually requires intravenous administration of narcotics in an emergency room setting for acute situations. Similar classes of drugs may be reasonably effective orally in an outpatient setting for less severe discomfort where nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories or narcotics like codeine can be prescribed. Some doctors will give patients with recurring passing of small stones a small supply prescription for hydrocodone to avoid a future visit to the ER when the next episode occurs. Taken at the first sign of pain, hydrocodone can eliminate much of the acute pain, nausea and vomiting which necessitates the hospital visit and still facilitate stone passage, although a follow-up with a physician is still necessary.

Patients who are to be treated non-surgically, may also be started on an alpha adrenergic blocking agent (such as Flomax, Uroxatral, terazosin or doxazosin), which acts to reduce the muscle tone of the ureter and facilitate stone passage. For smaller stones near the bladder, this type of medical treatment can increase the spontaneous stone passage rate by about 30%.

After treatment, the pain may return if the stone moves but re-obstructs in another location. Patients are encouraged to strain their urine so they can collect the stone when it eventually passes and send it for chemical composition analysis which will be used along with a 24 hour urine chemical analysis test to establish preventative options.

Urologic interventions

Most kidney stones do not require surgery and will pass on their own. Surgery is necessary when the pain is persistent and severe, in renal failure and when there is a kidney infection. It may also be advisable if the stone fails to pass or move after 30 days. Finding a significant stone before it passes into the ureter allows physicians to fragment it surgically before it causes any severe problems. In most of these cases, non-invasive Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) will be used. Otherwise some form of invasive procedure is required; with approaches including ureteroscopic fragmentation (or simple basket extraction if feasible) using laser, ultrasonic or mechanical (pneumatic, shock-wave) forms of energy to fragment the larger stones. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy or rarely open surgery may ultimately be necessary for large or complicated stones or stones which fail other less invasive attempts at treatment.

A single retrospective study in the USA, at the Mayo Clinic, has suggested that lithotripsy may increase subsequent incidence of diabetes and hypertension, but it has not been felt warranted to change clinical practice at the clinic.

More common complications related to ESWL are bleeding, pain related to passage of stone fragments, failure to fragment the stone, and the possible requirement for additional or alternative interventions.

Ureteral (double-J) stents

One modern medical technique uses a ureteral stent (a small tube between the bladder and the inside of the kidney) to provide immediate relief of a blocked kidney. This is especially useful in saving a failing kidney due to swelling and infection from the stone. Ureteral stents vary in length and width but most have the same shape usually called a "double-J" or "double pigtail", because of the curl at both ends. They are designed to allow urine to drain around any stone or obstruction. They can be retained for some length of time as infections recede and as stones are dissolved or fragmented with ESWL or other treatment. The stents will gently dilate or stretch the ureters which can facilitate instrumentation and they will also provide a clear landmark to help surgeons see the stones on x-ray. Discomfort levels from stents typically range from minimal associated pain to moderate discomfort.

Prevention

Preventive strategies include dietary modifications and sometimes also taking drugs with the goal of reducing excretory load on the kidneys:

- Drinking enough water to make 2 to 2.5 liters of urine per day.

- A diet low in protein, nitrogen and sodium intake.

- Restriction of oxalate-rich foods, such as chocolate, nuts, soybeans, rhubarb and spinach, plus maintenance of an adequate intake of dietary calcium. There is equivocal evidence that calcium supplements increase the risk of stone formation, though calcium citrate appears to carry the lowest, if any, risk.

- Taking drugs such as thiazides, potassium citrate, magnesium citrate and allopurinol, depending on the cause of stone formation.

- Some fruit juices, such as orange, blackcurrant, and cranberry, may be useful for lowering the risk factors for specific types of stones.

- Avoidance of cola beverages.

- Avoiding large doses of vitamin C.

For those patients interested in optimizing their kidney stone prevention options, it's essential to have a 24 hour urine test performed. This should be done with the patient on his or her regular diet and activities. The results can then be analyzed for abnormalities and appropriate treatment given.

No comments:

Post a Comment